IT WAS A JOURNEY that was never meant to be a quest. Yet, life turned it into one — aided by a single, inspiring phrase from an influential voice, along with a touch of the divine.

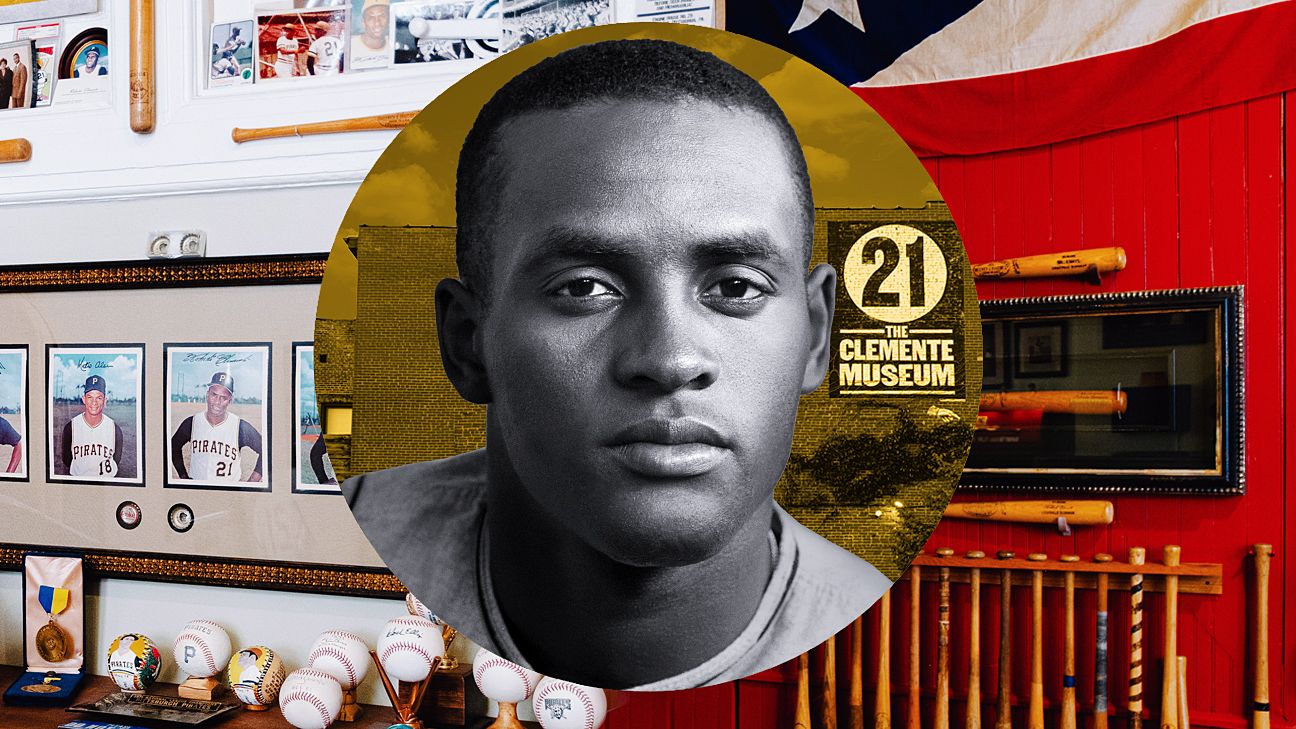

Nearly two decades ago, Vera Clemente, the widow of the iconic Roberto Clemente, visited the studio of photographer Duane Rieder ahead of the 2006 All-Star Game, set to take place at Pittsburgh’s PNC Park. This studio, once an old firehouse known as Pittsburgh’s Engine No. 25, is located in the Lawrenceville neighborhood. Built in 1896, the building had been condemned until Rieder purchased it from the city in 1994 for just one dollar.

Rieder was organizing a pre-All-Star celebration for the Clemente family and had decorated his studio with captivating photos of Clemente, as well as a collection of memorabilia he had gathered over the past decade. He had first met Vera after he produced a calendar featuring Clemente’s images to mark the last All-Star Game at Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium in 1994. The following year, he had helped Vera restore damaged photographs from the Clementes’ visit to the White House with President Nixon after the 1971 World Series, an event that elevated Roberto Clemente’s status nationally, confirming his place as a transcendent talent after 16 seasons of acclaim in the local arena.

Editor’s Picks

2 Related

The photographs held immense significance for Vera, who endured the loss of her husband during one of the most tragic events in American sports history. On New Year’s Eve in 1972, Clemente’s ill-fated plane, which was carrying relief supplies for earthquake victims in Nicaragua, crashed into the Atlantic shortly after departing from Puerto Rico. Following this catastrophe, financial strains and disrespect followed, with locals stealing valuable belongings from the Clemente family home in Puerto Rico, including the wedding album of Vera and Roberto.

Upon entering Rieder’s studio, Vera was struck by the stunning images of Clemente displayed on the walls, including “Angel Wings,” a renowned photograph capturing Clemente reaching for a catch while clouds behind him appear to morph into a pair of wings.

“Duane,” Rieder recalls Vera saying, “You ought to turn this place into a museum.”

Rieder responded by gifting Vera a priceless treasure he had obtained through years of “calling in favors” and a touch of luck — a photo album containing images from her wedding that she had never previously seen.

Just under two months later, the Clemente Museum opened its doors, breathing new life into a building once deemed unworthy.

“I owe a great deal of credit to Roberto and the Big Guy upstairs,” Rieder remarks, “for the wonderful things that unfolded in this building.”

<img class=" lazyload lazyload" data-image-container=".inline-photo" height="384" width="570"

Priceless memorabilia from the museum, such as Clemente’s game-worn and signed cleats, glove, and road bag, has been gathered over the years to offer visitors an authentic glimpse into the life of the baseball icon. Aaron Ricketts for ESPN

THE CLEMENTE MUSEUM

THE CLEMENTE MUSEUM spans 12,000 square feet and serves as a tribute to the man who has been referred to as “The Great One” in Pittsburgh for over fifty years. Rieder notes that approximately 10,000 guests visit the museum each year. This nonprofit establishment operates independently from the Pirates or Major League Baseball, relying on donations from passionate baseball fans, particularly dedicated Clemente enthusiasts. Rieder gives credit to Eddie Vedder, the lead singer of Pearl Jam, for helping keep the museum afloat during the pandemic. Of course, significant recognition also goes to the hard work and dedication of the museum’s owner.

The Clemente Museum is open for visits by appointment only and primarily operates on an honor system. Most of the 650 items related to Clemente are not behind glass cases, trusting visitors to refrain from touching or removing items. The museum is housed in a converted firehouse that exudes a dark and somber ambiance with its heavy wooden features, evoking the spirit of the 19th century characterized by handlebar mustaches and horse-drawn fire carriages. Some remnants of the old firehouse still exist, including two openings in the first-floor ceiling — one of which retains its fire pole while the other was removed to accommodate the entrance door.

When illuminated, the museum transforms into a shrine reflective of Pittsburgh’s unique character as a baseball town since 1882. Fans, celebrities, and major league players often treat the museum as a pilgrimage and sanctuary. Padres third baseman Manny Machado typically spends at least one night per season at the museum. Nearly every visiting team makes a late-night stop after games to honor The Great One and enjoy the basement, which features a speakeasy-style winery, wood-fired oven, and a cigar bar named after Pirates catcher Francisco Cervelli. Many players take turns swinging the imposing 38-ounce bat that 5-foot-11, 175-pound Clemente used. During a recent four-game series with Washington, 34 members of the Nationals visited the museum, including Darren Baker, 25, who made his major league debut this month. He found it amusing to spot a 1968 photo of a 19-year-old Dusty Baker in the Marines on the wall — legend has it that Dusty set a pull-up record for Marines that Clemente held. Dusty is, of course, Darren’s father and a legend in his own right. However, behind every anecdote, irony, and eerie coincidence that suggests the museum was destined to exist, there are three decades of hard work that provide depth to these stories, making them resonate with authenticity.

Without Rieder, who at 63 years old possesses the spirit of a college freshman, personally undertaking the restoration — from pulling electrical wires to removing part of the ceiling to reveal the original Carnegie Steel beam emblazoned with the number 21, indicating the beam’s 21-inch thickness — these coincidences might have remained hidden or, worse, erased forever by time and progress.

“The stories come to this building because we saved it,” Rieder reflects.

When the firehouse closed in 1972 — largely due to aging infrastructure and because new fire trucks were too large to pass through the wooden doors of a 19th-century building — Engine 25 became a base for EMS vehicles. By the early 1990s, the structures were falling apart, and the city had agreed to demolish over a dozen old firehouses. Engine 25 had been condemned when Rieder first considered purchasing it. He describes it as a “haven for pigeon droppings and rats.”

“This part of town, Lawrenceville, was a disaster,” he recalls. “People thought I was insane for buying here. The neighborhood was in such disrepair that parking on the street was a risky move … and the building required extensive renovations. There was no running water, and I was looking at estimates pushing $500,000.”

In 1994, Rieder opted for another studio in Polish Hill. The paperwork was finalized, and the deal was closed. Engine No. 25 was slated for an alternative fate that the irate residents of Lawrenceville opposed: it was set to become a nightclub. There seemed to be no way out until Jimmy Ferlo, the influential city councilman for the 7th District, intervened. “I told Jimmy, ‘There’s no way

“We’ve closed,” Rieder recalls. “Jimmy asked, ‘Do you want it, yes or no?'” In a scenario that feels straight out of a film, Ferlo tore up Rieder’s closing documents for the Polish Hill location, and the transition to the firehouse miraculously occurred.

The Clemente Museum is situated in the historic Engine House No. 25 in the Lawrenceville area of Pittsburgh. The founder acquired the building for just $1. Aaron Ricketts for ESPN

The firehouse carries a somber twist of fate: Engine No. 25 officially ceased operations on December 31, 1972, at 9 p.m. ET; meanwhile, a thousand miles away, Clemente’s plane had just taken off and began its tragic descent about 20 minutes later. Undeterred, Rieder undertook the renovation of the structure, piece by piece. A welder by profession, who describes himself as “severely dyslexic,” Rieder dedicated himself to the building’s restoration. He sanded floors, scavenged for timber and coal, refurbished the original tin panels that enhance the second-floor ceiling, discovered old items like a filing cabinet from a nearby printing press, and saved treasures such as the Angel Wings photographs from the trash.

The following year, Rieder met Vera Clemente and began archiving materials related to Clemente. A vision for a museum was forming, but it did not fully materialize until Vera Clemente suggested it more than a decade later.

“If I hadn’t been a photographer and a workaholic, this wouldn’t have been possible,” Rieder states. “Who else could achieve this? Even with unlimited financial resources, could you really make this happen? It wasn’t about money. And I’m not boasting when I say this; it was simply about dedicating yourself to your interests, piece by piece.”

When the museum opened its doors in 2006, Rieder had spent twelve years working on the building. During that time, he also learned another skill: winemaking. Initially photography, then wine, and baseball. “Every Italian in Pittsburgh made their own wine,” he recalls. “I began making dago red as a hobby.” Today, major league players like Pete Alonso, Ryan Zimmerman, and Josh Bell have barrels of wine in the cellar speakeasy, part of Rieder’s wine club.

Sarah Kelsey, a part-time employee at the museum with a calming voice and gentle presence, did not come to the Clemente because of baseball. Originally hailing from Arlington, Virginia, she sought a fresh start and moved to Western Pennsylvania seven years ago. She now describes the region—and the Clemente—as a tranquil haven. She met Duane Rieder through wine, but stayed for the architecture, the community, and what she refers to as the building’s enchanting spirit—the cherry floors in the basement, slightly sloped to the right because the firehouse, built in 1896, once served as a horse stable before the era of fire trucks.

On the second floor, light streams into the spacious room, reminiscent of stained glass, highlighting the wide-plank floors and original woodwork. The second floor is a treasure trove for Clemente enthusiasts: it houses the 1961 silver bat honoring his first batting title, which is dented because his children used it to play. For Kelsey, the museum is a sanctuary. “It is a stunning building,” she remarks. ”The building exudes a sense of safety. Each time I visit, I discover something new or hear a different story. It is a profoundly uplifting space. People find it moving. I feel fortunate and humbled to be here. When visitors come, they want to share their stories. They express a desire to donate items—albums, cuff links. They feel compelled to give.”

The museum has been rescued three times, by chance or divine intervention. In 2006, Rieder’s most notable photo—depicting the Steelers praying before a game—went viral after a local news station featured him before the Steelers-Seahawks Super Bowl. The sale of the iconic print enabled Rieder to rectify a tax accounting error that had put him in debt. “I paid off the IRS,” he states. “Sixty thousand. In cash.”

In 2009, disaster nearly struck when the museum almost burned down. “That was my fault,” Rieder admits. “I was working on the plumbing. I heated copper pipes with a torch, and it ignited the insulation and caught fire.”

The power suddenly went out, engulfing me in complete darkness. In that moment, I spotted a ball of fire behind the drywall. I reacted instinctively and punched holes in the drywall with my fist until I reached the insulation and extinguished the flames. Afterward, I repaired the pipe and returned home.

During 2020, the pandemic nearly forced the shrine to shut down. However, Eddie Vedder came to the rescue. “He recorded a video for us, essentially a virtual fundraiser,” Rieder recalls. “He also sent us a guitar signed by the entire band. We auctioned everything off and managed to raise $100,000.”

“We faced nearly two years of closure while our bills kept accumulating. Eddie supports around a hundred charities, and we were fortunate to be included among them. So, we are truly grateful for Eddie Vedder.”

Clemente, who has Afro-Latino roots, made his major league debut in 1955, eight years after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in MLB. Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

THE LEGACY OF ROBERTO CLEMENTE

IN THIS CITY, Roberto Clemente is celebrated like no other player in any major league town. He is not merely revered like Ruth, Williams, or Mays—whose talents evoke admiration and nostalgia. Almost 70 years after his debut and 52 years after his passing, Clemente is cherished closer to the status of Henry Aaron; he’s not just regarded with respect but held in deep reverence. The main bridge across the Allegheny River leading to PNC Park is named the Roberto Clemente Bridge, with a statue of Clemente situated at its foot. Within the stadium, attractions for children, a bar in center field for adults, and perhaps the finest views in baseball—enhanced by the excitement brought by rookie sensation Paul Skenes—are all present. Yet, it’s the images of Clemente throughout that ground the experience of watching a game here. In the team shop within the stadium, Clemente jerseys remain prominently displayed. He is the moral compass of the city.

Art Rodriguez, a retired dentist with a nearly ancestral tie to the museum, leads many of its private tours. He still possesses the scorecard from his very first baseball game: July 28, 1968, at Forbes Field, where the Cardinals faced off against the Pirates, who won 7-1. Clemente, whose roots trace back to a cane crop worker, went 3-for-4 that day, hitting a triple and scoring two runs. Rodriguez and his father, Archie, ceased recording the Cardinals’ scores after the second inning. However, their attention remained on the Pirates until the sixth inning when Clemente struck out, ending their turn at bat. Bob Gibson pitched that day; yet, Rodriguez vividly remembers the aura of Gibson as he sought an autograph—green turtleneck, gold chain—but left empty-handed. Rodriguez was just seven years old at the time.

Growing up in Donora, approximately 30 miles from Pittsburgh—the birthplace of the renowned Stan Musial and Ken Griffey Jr.—Rodriguez discovered his family’s connection to baseball through Musial. It was also work that drew his family to Pittsburgh. His paternal grandfather, Manuel, immigrated from Oviedo, Spain, in 1917 to labor in the Pennsylvania zinc mills. On his maternal side, his grandfather, Dominic, emigrated from Ceto, Italy, in 1913 and worked in the coal mines. Their narratives embody the immigrant-American experience: one grandparental lineage from Spain and the other from Italy, with limited English skills and a disinterest in sports. The subsequent generations found their American identity through sports, with Musial connecting the father and son to Clemente.

During his tours, Rodriguez chooses not to bask in Clemente’s impressive statistics—a .317 career batting average, 3,000 hits, four batting titles, and 12 consecutive Gold Glove awards—as much as he aims to highlight Clemente’s dignity and the struggles he faced during his era. Clemente experienced the discrimination directed at Black players and the prevalent anti-Latin sentiments within baseball. Media personnel would represent Spanish-speaking athletes phonetically, almost mocking their English skills. Clemente deeply resented efforts to Americanize his name; several editions of his baseball cards listed him as “Bob Clemente” instead of “Roberto.” Over the years, he wrestled with those grievances before confronting his teammates as both athletes and individuals.

“I place a significant emphasis on the racism he endured, yet he remained incredibly stoic,” Rodriguez remarks. ”He had an incredible way of reaching people. He recognized that he needed to speak out. He conveyed that a person who harbors bigotry can’t truly be a good man, and that message resonates deeply.”

to the messages of today.”

During his tours, Rodriguez perceives moments when visitors draw connections between the xenophobia Clemente experienced in his career and today’s national divisions. Prior to winning the hearts of the baseball community through his talent and humanitarian efforts, Clemente faced a growing sentiment in the sport that too many minorities were being hired. Despite the excellence of Clemente, Mays, and Aaron, there were voices claiming that integration was diminishing the game.

“If you’re Black or an immigrant, the underlying message is ‘You have ruined our country,’ and that resonates,” Rodriguez remarks, referencing the escalating political discourse of recent years and its similarities to Clemente’s era. “Coming from a family of Spanish and Italian immigrants, I can relate to the targets of those comments. While he didn’t voice it, nor did his supporters, that sentiment was palpable. I am astonished by it. Had someone told me that racism would resurface to the extent we see today, akin to Clemente’s time, I would not have believed it. It’s crucial for the younger generation to grasp this.”

Clemente remains an unforgettable part of American mythology, just as baseball and Pittsburgh are. This reverence comes from the unique individual who lived as he died, maintaining significance over time. The Pirates celebrated two World Series victories during Clemente’s tenure, yet their story and his legacy remain uncomplicated, especially in contrast to the Steelers of the 1960s, who were not yet the powerhouse they would eventually become. Pittsburgh, known as the Steel City, represents unpretentiousness and integrity—qualities often aspired to but not always exemplified.

Duane’s wife, Kate, certainly embodies those qualities. She is a shy yet humorous woman, contemplative yet expressive, revealing less than her thoughts. While people refer to her husband as “the mayor of Pittsburgh” for his boundless sociability and constant presence, Kate Rieder is his counterbalance, often tempering Duane’s generous nature. It is not uncommon for the Rieders to receive late-night calls from MLB players or coaches—such as Nationals manager Davey Martinez—eager to visit the museum for cigars, drinks, and to soak in the legacy of The Great One. “I’m not one for public engagements,” she shares. “I’m fine as long as I can avoid it.” Raised in the South Hills area, Kate experienced a slice of her childhood anew. Her father, the iconic meteorologist Bob Kudzma, was an old New Englander and devoted Red Sox supporter from Nashua, New Hampshire, who became a beloved figure in Pittsburgh. Kudzma spent 34 years on the air, yet unlike the naturally outgoing Duane, Kate recalls her father as a private man with a public role. Off-camera, he preferred solitude and family time.

She expresses admiration for Duane’s vigor. ”He always manages to create everything. He never takes a break. He assists others and is incredibly thoughtful. He’s like the Energizer Bunny.”

Nick Barnicle, a film producer who documented Duane’s Clemente collection and spent significant time with them at the museum, remarked, “Kate is the Landau to Duane’s Springsteen. The Robin to Duane’s Howard. The Varitek to Duane’s Pedro. Without Kate, it’s just not the same.”

Duane Rieder, owner of the Roberto Clemente Museum, stands in front of a mural outside his establishment. Aaron Ricketts for ESPN

THE PROPELLER

BRIAN, THE UBER DRIVER driving me to the museum on a recent late-summer day, remains silent for several blocks before checking his phone for my destination again. “The Clemente Museum,” he states flatly. There’s a curious monotone in his voice—something is weighing on his mind. After several red lights, Brian finally divulges his unease. “The propeller is in there,” he informs me. “It’s right there. That has never sat well with me.”

To the left of the museum’s main entrance, around the position of 11 o’clock, lies a vertically rectangular plexiglass case sheltering a solitary, damaged gray-black propeller blade. This blade is one of the remnants from the DC-7 that tragically took Clemente’s life as it went down in the Atlantic. Following the crash, the newspapers displayed the

Photos from Puerto Rico capture the heartbreaking search and rescue efforts. One of the most striking images shows Pirates catcher Manny Sanguillén, the sole teammate who ventured into the ocean during the mission, wading waist-deep through the surf, visibly distraught.

In 2013, the St. Louis Cardinals visited Pittsburgh, and during that time, Carlos Beltrán, the celebrated outfielder and part of the legacy of illustrious Puerto Rican players, explored the museum. Shortly after his visit, Beltrán shared an intriguing discovery with Rieder: the father of one of his friends had captained the Coast Guard vessel responsible for retrieving the plane wreckage from the ocean.

“Not long after, I received a call from Carlos’s friend, an architect named Angel, who was collaborating with Carlos on his academy design,” Rieder recalls, gazing into the display case. “He said, ’Sit down. I have a picture to show you.’ A photo of a propeller appeared. It was stored in his friend’s garage. He asked, ‘Would you like this?’ I was stunned and responded, ‘Could that be the propeller from the plane?'”

Rieder secured the propeller blade at the close of 2013, and the following year, it became a permanent exhibit in the museum. However, he had to first address a crucial decision regarding its display — whether showcasing the blade was essential or superfluous — during a poignant meeting with Vera Clemente and her three sons, Maurice, Ricky, and Roberto Jr.

“A Puerto Rican auction house had been selling off parts from the plane,” Rieder explains. “The family pleaded for those items to be removed from the auction. Later on, they were coming to Pittsburgh to discuss Clemente Day. I mentioned that I had something I wanted to discuss and let them vote on its display. If they decided it should remain, it would; if not, it would be set aside. So, they arrived, and I had the blade in the center of the room, covered with a black cloth. I unveiled it, and Vera, Maurice, and Ricky all agreed, saying, ‘Yes, it should be here.’ A museum ought to tell the truth and share the narrative. Roberto Jr. became very emotional and hurried out the door.”

Rieder had his own motivation for displaying the propeller: to counter the misconception that the plane was never recovered. “It is true that Roberto’s body was never discovered,” he acknowledges. “However, during our numerous tours, someone always claims that the plane was never located. All Puerto Ricans are aware that the plane was found. They observed the Coast Guard retrieving parts over three days from the deck, where it originated.”

Vera passed away in 2019, and Rieder ultimately reached an arrangement with Roberto Jr.: whenever he visited, the museum would cover the propeller and hide it from view. One day, Roberto Jr. came into town on short notice. With no time to relocate the blade, Rieder rushed to conceal it with a poster.

“The posters weren’t high enough,” Rieder recalls. “He entered and said, ‘I’m alright with it now.’ It took him several years, but he accepted that it’s part of the narrative. They found the plane.”

RETIRE NO. 21

ON THE COUNTER of the museum, adorned in Pirate black-and-gold, circular stickers proclaiming “RETIRE 21” call for Major League Baseball to honor Clemente similarly to Jackie Robinson and the approach taken by the National Hockey League for Wayne Gretzky: by universally retiring Clemente’s legendary No. 21.

The initiative to retire the number stems from a grassroots movement that resonates deeply with its supporters — no player embodies greater inspiration for the Latino athletes now prevalent in the sport than Clemente, the first Latino to be enshrined in the Hall of Fame. However, Major League Baseball has not officially endorsed this idea, as the universal retirement of a jersey number is exceedingly rare. When baseball decided to retire Robinson’s No. 42 during the 50th anniversary of his debut in 1997, it sparked controversy. This decision did not originate from the commissioner’s office but rather from National League president Len Coleman.

The league office asserts that Clemente is sufficiently honored via the Roberto Clemente Award, which is presented annually to the player who exemplifies exceptional community and humanitarian service. Nevertheless, the notion of retiring Clemente’s number has captured the interest of the Major League Baseball Players Association. Executive director Tony Clark expressed his support for the retirement of Clemente’s number, preferring that the players take the initiative themselves, rather than waiting for directives from the league.

While the commissioner’s office may have retired the number, Clark hopes that players will come together to unanimously stop wearing No. 21. According to Clark, such a collective decision would make for an even more significant gesture.

Fans and fellow players have urged Major League Baseball to retire Roberto Clemente’s No. 21 alongside Jackie Robinson’s No. 42. Aaron Ricketts for ESPN

THE PLACE TO BE

THE CLEMENTE MUSEUM stands out as a must-visit location for out-of-town visitors seeking to impress, as well as for celebrities and dignitaries paying their respects—and enjoying the winery located downstairs. Eddie Vedder has a reserved table, and one chair bears the name ”Smokey,” a nod to Smokey Robinson, who once sat and drank there. (“I make a semi-sweet Riesling for him,” Rieder mentions.)

This year, politically, Pennsylvania has emerged as a battleground state, flooded with attack advertisements from both major political parties. Most analyses predict that Pennsylvania will play a critical role in the 2024 election. Thus, during a late-summer week, Democratic presidential nominee Kamala Harris stops by as part of her campaign, including a visit to the Clemente Museum on her short list of local spots.

Although Harris isn’t present on the day of my visit, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack, a native of Pittsburgh, makes an appearance. Accompanied by two Secret Service agents, the 73-year-old Vilsack and his wife, Christie, explore the museum before settling into the basement for wine and storytelling. Vilsack served as the governor of Iowa from 1999 to 2007 and hails from the Squirrel Hill neighborhood.

As Vilsack savors his wine, the Secret Service maintains a discreet presence nearby. Occasionally, he gathers another intriguing piece of the museum’s history from Rieder—often whimsical tidbits that seem too outlandish to be true, such as claims about Lou Gehrig sleeping at the firehouse during the 1927 Yankees-Pirates World Series. “OK, now you’re pulling my leg,” Vilsack remarks, amused by the impossible legends.

“First of all, who could ever fact-check that but me, because I’m here in a building that we preserved,” Rieder responds. “Now, people are coming for Clemente tours, and a woman mentioned on a tour that her father was the chief who shut this place down. If I hadn’t invited her to share that story and brought her father here, we would have lost that connection. We accomplished something meaningful, and it wasn’t intentional; I was merely seeking a location for my studio.”

Clemente represents more than just baseball. He embodies America and Pittsburgh itself. Across the table from Vilsack sits a wine barrel with the distinct silhouette of Bruno Sammartino, the iconic professional wrestler who moved to Pittsburgh as a teenager. Rieder shares a 1967 Polaroid photo featuring both Clemente and Sammartino, where the caption reads, “Bruno & Roberto,” alongside their weights: 275-175. Vilsack nods in recognition, yielding to the impact of this hallowed space and ultimately decides to purchase four bottles of wine to take with him.

“This is truly a tribute to a man who has been gone for 50 years,” Vilsack reflects. “I’ve encountered things here that I never anticipated seeing.”

Beyond the Diamond: The Clemente Museum and the Legacy of a Baseball Icon

Roberto Clemente, a name synonymous with baseball brilliance and humanitarian efforts, transcended the sport to become an enduring symbol of excellence and compassion. Nestled in the heart of Pittsburgh, the Clemente Museum serves as a shrine to his remarkable legacy, showcasing not only his unparalleled achievements on the field but also his profound impact off it. This article explores the Clemente Museum, the life of Roberto Clemente, and how his legacy continues to inspire generations.

The Clemente Museum: A Treasure Trove of History

Located in the historic neighborhood of Lawrenceville, the Clemente Museum is dedicated to preserving the legacy of the Hall of Famer. Opened in 2006, the museum is situated in a renovated church and features an extensive collection of memorabilia that tells the story of Clemente’s life, career, and humanitarian contributions.

Exhibits and Collections

The museum houses a variety of exhibits, including:

- Game-Worn Jerseys: Explore the jerseys worn by Clemente throughout his illustrious career.

- Historic Artifacts: Discover items ranging from baseballs and bats to personal letters and photographs.

- Interactive Displays: Engage with multimedia presentations that highlight key moments in Clemente’s life.

Special Events and Programs

The Clemente Museum hosts various events throughout the year, including:

- Educational Workshops: Programs aimed at teaching youth about Clemente’s values, sportsmanship, and community service.

- Annual Celebrations: Commemorative events on the anniversary of Clemente’s passing that honor his legacy.

- Guest Speakers: Talks by former players, historians, and community leaders who share insights into Clemente’s life.

The Life and Legacy of Roberto Clemente

Roberto Clemente was born on August 18, 1934, in Carolina, Puerto Rico. He began his professional baseball career in the late 1950s and quickly became a star player for the Pittsburgh Pirates. His combination of skill, speed, and agility made him a formidable force on the field.

Career Highlights

| Year | Achievement |

|---|---|

| 1960 | World Series Champion |

| 1971 | World Series MVP |

| 1972 | 3000th Career Hit |

| 1973 | Inducted into Hall of Fame (posthumously) |

Humanitarian Efforts

Beyond his athletic prowess, Clemente was deeply committed to humanitarian work. He dedicated his life to helping others, especially in his home country of Puerto Rico. Some of his notable contributions include:

- Disaster Relief: Clemente organized relief efforts for victims of earthquakes and other disasters in Latin America.

- Community Development: He advocated for youth programs and education initiatives in Puerto Rico.

- Advocacy for Latino Players: Clemente fought for the rights and recognition of Latino players in Major League Baseball.

Visiting the Clemente Museum

For those looking to immerse themselves in the life of Roberto Clemente, a visit to the Clemente Museum is a must. Here are some practical tips for making the most of your visit:

Visitor Information

- Location: 3339 Penn Ave, Pittsburgh, PA 15201

- Hours: Open Wednesday to Saturday, 10 AM – 5 PM

- Admission: Adults $10, Students & Seniors $5, Children under 12 free

Tips for a Memorable Experience

- Book a Guided Tour: Enhance your visit by joining a guided tour for in-depth insights.

- Engage with Staff: Don’t hesitate to ask questions; the staff are passionate and knowledgeable.

- Plan for Special Events: Check the museum’s calendar for any special events or guest speakers during your visit.

Case Studies: Clemente’s Impact on the Community

Roberto Clemente’s influence extends beyond baseball. His humanitarian efforts set a standard for athletes, making him a role model for many. Here are a couple of case studies highlighting his impact:

Clemente’s Influence in Puerto Rico

In the wake of the devastating 1972 earthquake in Nicaragua, Clemente organized a relief mission to provide aid to families affected by the disaster. He personally oversaw the delivery of supplies, demonstrating his commitment to helping those in need.

Legacy of Philanthropy

Clemente’s legacy of giving lives on through the Roberto Clemente Foundation, which continues to support a variety of charitable endeavors, including education, sports, and health initiatives in Puerto Rico and the United States.

First-Hand Experience: A Visit to the Museum

Visitors often leave the Clemente Museum with a deeper appreciation for not just a sports icon but a transformative figure in American history. One visitor remarked, “Walking through the museum felt like stepping into a time capsule. The stories, the memorabilia, and the passion behind it all made me feel connected to Clemente’s spirit.”

Personal Connections

The museum encourages visitors to share their own stories and connections to Clemente, further enriching the experience for all. This interaction fosters a sense of community and shared appreciation for his legacy.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Roberto Clemente

The Clemente Museum stands as a testament to the life and legacy of Roberto Clemente, a baseball icon whose influence continues to inspire future generations. Through its exhibits and programs, the museum educates visitors on the significance of Clemente’s contributions both on and off the field. For anyone interested in baseball history, humanitarian efforts, or the spirit of giving, a visit to the Clemente Museum is a rewarding experience that highlights a true legend.